(Not only is this woefully, frustratingly, absurdly belated, but it’s also not yet finished. But I hate being a blog tease, so here’s part one!)

If you’ve been following along with the previous China Study entries (and the wild drama that ensued), you know that I’ve been promising an entry on wheat for a while now, mostly because this little snippet snagged so many eyes:

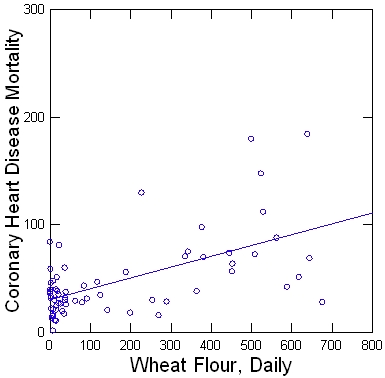

Correlation between wheat flour and coronary heart disease: 0.67

That’s a value straight from the original China Study data. Could the “Grand Prix of epidemiology” have accidentally uncovered a link between the Western world’s leading cause of death and its favorite glutenous grain? Is the “staff of life” really the staff of death? Bwah ha ha.

Damning as it seems, a single unadjusted correlation isn’t enough to make that leap. Actually, nothing in this post will be enough to make that leap, because A) it’s epidemiological data and not a controlled study, and B) correlation isn’t causation anyhow. You know the drill.

So my goal here isn’t to prove anything about wheat. Mostly, I want to see if I can find a confounder that’s creating a false association between wheat and heart disease in the China Study data. Something wheat-eating regions have in common that makes them more susceptible to ticker troubles. Because really, folks, this is serious business:

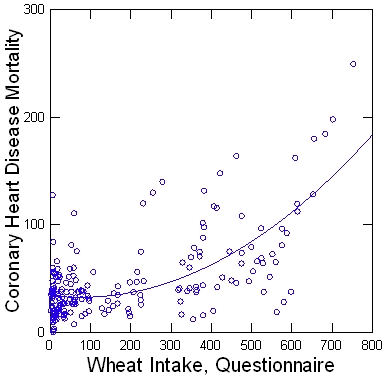

And when we pluck out the wheat variable from the 1989 China Study II questionnaire—which has more recorded data—and consider potential nonlinearity, the outcome is even creepier:

Wowza! By the way, wheat flour also correlates significantly with hypertensive heart disease and stroke, but I’m mainly going to look at coronary heart disease in this post. (And although wheat looks like it could have a nonlinear relationship with heart disease, with the highest wheat eaters having disproportionately steeper rates than non-wheat eaters, I’m going to treat it as linear for the sake of this analysis. That way, the worst that’ll happen is we’ll underestimate the potential effect of wheat, which—for now—is better than overestimating it.)

Since I’m not trying to dissect our friend Campbell’s claims anymore, I’ll be using the China Study II data (from 1989) because it recorded more descriptive variables about diet and blood samples.* And because it’s already available online. (Not that I don’t love typing thousands of numbers onto my computer by hand. Three cheers for data-entry-induced carpal tunnel!)

*Quickie note: If you want to play with the China Study numbers yourself, I recommend not just using the “all vascular diseases” variable, because it includes rheumatic heart disease—a condition spawned by rheumatic fever and generally unrelated to diet. Lumping diseases with different etiologies together dilutes the strong correlations you can find by looking at each disease independently. Try checking out stroke (M065 STROKE), ischaemic heart disease (M063 IHD), and/or hypertensive heart disease (M062 HYPTENS) along with all vascular diseases (M059 ALLVASC).

Here’s the problem with looking at wheat and heart health. Along with correlating pretty darn strongly with heart disease, wheat-eating regions boast a number of other factors possibly involved as well—some as protective agents and some as causative. For instance, wheat flour correlates significantly and inversely with:

- Plasma folate concentrations (and consequently, homocysteine status)

- Fish intake and DHA levels

- Yearly green vegetable consumption

- HDL cholesterol

- Vitamin C intake

And it correlates significantly and positively with:

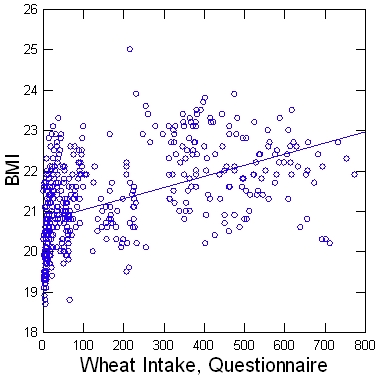

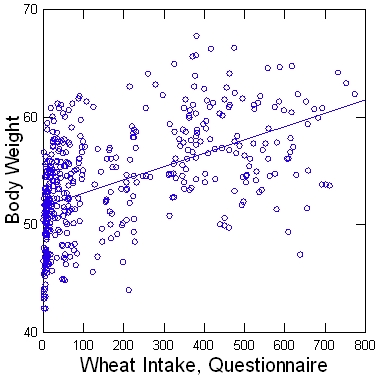

- Height, weight, and BMI

- Blood pressure

- Latitude (as a possible marker for vitamin D status)

- Yearly milk intake

- Polyunsaturated fatty acid intake

Since all of these variables also associate (inversely or positively) with heart disease, it’s possible they could be confusing the “0.67” figure we’ve cited for wheat. Could some other, non-grain component of the wheat eaters’ diets predispose these folks to heart disease?

On the bright side, China’s wheat eaters are less likely to drown than the wheat-shunners (r = -0.68 for the youngsters under 34). Maybe they’re all buoyant from celiac bloat.

And in case you’re wondering, here are some heart disease risk factors (the ones Conventional Nutritional Wisdom likes to toss around) that don’t positively correlate with wheat. That means we probably can’t blame ’em for wheat’s dirty deeds. Out of curiosity, though, I’ll still include them in some of my models just to see how they behave in relation to wheat with heart disease.

- All meat intake (r = -0.35)

- Red meat intake (r = -0.30)

- Animal fat intake (r = -0.35)

- Saturated fat intake (r = -0.40)

- Total animal protein intake (r = -0.27)

- Total fat intake (r = -0.43)

- Fat as a percentage of total calories ( r = -0.41)

- Total cholesterol (r = -0.05)

- Apolipoprotein B (r = 0.02)

- Daily alcohol intake (r = -0.37)

Mostly, what I’m looking for is a little somethin’-somethin’ that both wheat flour and heart disease have in common. A shared variable that could be slyly—and wrongfully—framing wheat as our heart-harming villain.

So how do we untangle all these variables? I’m using two methods: multiple regression analysis and stratification. Multiple regression is a handy way of looking at two or more variables and seeing how each one behaves when the others are held constant, and stratifying data can work similarly by divvying up data into groups that share or exclude a certain variable. (For the stats junkies out there, I’m using ordinary least squares for the regressions, and I’m running each model two times: once with the data as-is, and once with any non-normally-distributed dependent variables transformed (via natural log) for more reliable statistical significance testing. I’m also checking for linearity between the variables before creating each model, since a nonlinear relationship will be underestimated with linear regressions.)

And for anyone not familiar with statistics terminology, here’s a really quick rundown of what you need to know to understand the numbers in this post:

- r = the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient between two variables. It can range from -1 to 1. When it’s zero or close to zero, there’s pretty much no relationship between the variables. When it’s a negative number (like r = -0.50), there’s an inverse relationship between the variables, meaning one increases as the other decreases. When it’s a positive number (like r = 0.50), there’s a positive relationship between the variables, meaning they increase and decrease hand-in-hand. The closer to -1 or 1 r is, the stronger the association. R can never prove cause and effect, though—it only indicates an relationship of some sort.

- beta = the standardized coefficient for each variable in the multiple regressions I’ll be running. This is a lot like r, in the sense that it shows how well a specific variable is predicting the outcome (eg, heart disease) and also ranges from -1 to 1. But in the case of beta, we’re also controlling for the effects of other variables, so this number tends to be more accurate than r.

- p = the probability that our results are just a fluke. P indicates how likely it is that we’d get a value of a test statistic that’s as extreme (or more extreme) as the one we have based on chance alone. Having a p-value of less than 0.05 indicates a high level of significance and means that our results are pretty sound. The lower the number, the more confident we can be that we’ve got something legit.

- r-squared = percent of variance explained. This number shows what proportion of the outcome (eg, heart disease) can be explained by the variables in a particular model (eg, wheat and HDL cholesterol). The higher the number, the more successfully the variables are predicting the outcome. (“Predicting” is a misleading way of putting it, though, since we still aren’t looking at proof of cause-and-effect—only a relationship.)

Preliminary theories

It’s no secret that I’m less-than-enamored with wheat. We parted ways long ago (he got me allergic and then ran off with some floozy—classy, eh?). Nonetheless, I don’t like pointing fingers where they shouldn’t be pointed, so I’ll entertain some alternative theories that could explain wheat’s apparent association with heart disease.

1. Folate deficiency. In northern China, about 40% of the population qualifies as folate deficient (compared to only 6% in the south)—a geographical trend that corresponds nicely with wheat consumption. Being low in folate tends to elevate homocysteine, which—you guessed it—is an independent risk factor for heart disease. So maybe it’s not the wheat itself causing mischief, but the fact that low-vegetable, wheat-centered diets in China tend to breed folate deficiency and hike up homocysteine.

On top of that, in the China Study II data, wheat flour positively correlates (r = 0.30, p<0.05) with childhood death from neural tube defects—a category of birth defects often related to folate deficiency. Although the China Study data didn’t document homocysteine levels (darnit), the 1989 data did measure plasma folate. That means we’ll be able to test whether folate levels could be obscuring the true relationship between wheat and heart disease.

2. Vitamin D deficiency. For the most part, wheat-eating regions in China are in the northern half of the country—a hotspot for vitamin D deficiency, which is strongly linked to heart disease. Given the pretty convincing correlation between latitude and heart disease mortality, it’s possible that vitamin D is playing a role in this mess. Are the wheat-eaters merely suffering from low levels of the ol’ Sunshine Vitamin due to their unfortunate geographical placement, and getting more heart disease as a result? Sure seems possible.

3. Low intake of DHA. In an earlier publication, Campbell and his crew already determined that fish and DHA intake appears protective against heart disease in the China Study data. Not too surprising, since DHA reduces blood viscosity and can lower other factors associated with heart disease (like triglyceride levels). And considering wheat-eating regions don’t consume much seafood (r = -0.43 for daily fish intake), perhaps DHA deficiency—rather than wheat consumption itself—is to blame for higher rates of heart disease.

4. Combo-abombo. Maybe a mix of low folate, vitamin D deficiency, and DHA deficiency are swirling together into a doomful vortex—some horrible, Bermuda-Triangle-esque zone of heart disease. A zone that just happens to overlay areas of wheat consumption.

5. Unexpected mystery variable. If none of the above can explain the wheat-heart disease link, we’ve still got a verdant jungle of China Study variables to plow through. So plow we shall. I’ll try running a number of common-sense models to see if I can find something that explains heart disease better than wheat alone.

Multiple regression results

Folate. Ah, theory numero uno! Like wheat, folate has a strong, statistically significant correlation with heart disease (r = -0.40, p<0.001), so what happens when we run a model using both folate and wheat as exposures? Initially, it looks like wheat clobbers folate as a predictor (beta = 0.59, p<0.001 versus beta = -0.06, p = 0.39)—which would suggest that, although China’s wheat-eaters tend to have lower folate levels, folate deficiency itself isn’t enough to explain the link with heart disease.

But I’m not ready to dismiss this one just yet. As often happens with plasma measurements and health conditions, folate may have a nonlinear relationship with heart disease—which means multiple regressions (of the linear variety) won’t show the full picture. Indeed, when I make a scatter plot for folate levels and coronary heart disease, it looks like a bit of a curve emerges, with folate being most strongly associated with heart disease when the county average dips below 10 micrograms per liter (or thereabouts). Above that, the correlation is far less dramatic.

So how do we deal with this statistical monkey wrench? For starters, I tried transforming the folate data to make it more suitable for linear regressions, but that didn’t do diddly squat to the results: The numbers were beta = 0.58, p<0.001 for wheat and beta = -0.06, p = 0.31 for folate. So then I tried stratifying the data based on “low” and “high” folate levels (10 or less micrograms/liter versus 10.1 or more micrograms/liter), but both subgroups continued showing wheat as strongly and significantly correlated with heart disease while folate was off the hook.

Just to cover my bases (and because I’m a stubborn son-of-a-gun), I kept playing with the numbers for a while longer to see if I could excavate anything new. Nope. Bottom line: It looks like wheat is predictive of heart disease whether or not folate levels are low, whereas folate is mostly predictive of heart disease only in the presence of high levels of wheat consumption.

So, theory #1 doesn’t pan out. Bugger. But bear in mind, we’re using folate mostly as a marker for elevated homocysteine, so these results don’t mean that homocysteine itself isn’t playing a role. Other causes of high homocysteine, such as B12 deficiency, weren’t documented in the China Study data. So this is an issue that’ll have to remain annoyingly unresolved. Another bugger!

Onto the next theory: latitude. Could the folks living in northern wheat-eating regions have lower vitamin D levels, leading to more heart problems—and creating a false link between wheat and cardiovascular disease? I admit, this was my favored theory after folate, but it ain’t holdin’ water. When I run wheat and latitude together as potential contributors to heart disease, wheat remains strongly predictive (beta = 0.65, p<0.001), while latitude diminishes (beta = -0.01, p=0.96). It’s pretty clear that the raw correlation between heart disease and latitude (which is 0.43, p<0.01) is just an echo of the relationship between heart diseases and wheat-eating regions, which are typically northern.

Okay, so that’s two strikes for Denise’s heart disease theories. What about fish and DHA? Are the wheat eaters suffering due to their fishless (and low-in-DHA) diets rather than from wheat itself? Alas, it doesn’t look likely. When I run these things together as exposures for heart disease, wheat stays strongly predictive (beta = 0.68, p<0.001) while the fishies do not (beta = 0.08, p = 0.47). Likewise, DHA teeters out into statistical insignificance (beta = 0.06, p = 0.30) when used in a model with wheat.

(Wait, I know what you’re thinking! “Why does it look like fish and DHA contribute positively to heart disease?” It’s because many of the fish-eating regions are more industrialized, and—in the absence of wheat—the fish-heart disease relationship is confounded by other factors like more desk work, more smoking (especially manufactured cigarettes), less physical activity, more vegetable oil consumption, and so forth. When we add some more variables to the model that take away the “city effect” associated with fish—such as apo-B, tobacco use, or percentage of the population employed in agriculture—then both fish and DHA turn inverse again. Although wheat, it should be mentioned, stays rock-steady in its high coefficient and statistical significance.)

Other stuff

Milk. Is moo juice a cardiovascular foe obscuring the relationship between wheat and heart disease? Probably not, according to the data—which isn’t surprising, given how few counties even drink the stuff. When running daily milk intake alongside wheat intake, wheat keeps its positive correlation (beta = 0.67, p<0.001) and milk actually turns a bit inverse, though not significantly so (beta = -0.07, p=0.47). No model shows a significant association between milk and cardiovascular disease, so I’m crossing this one off the list of potential confounders.

Blood pressure, BMI, corn, millet, sorghum, rice, added animal fat, added vegetable fat, total fat, total animal food, total carbs, total protein, percent of calories from animal protein, and all the smoking/tobacco variables I tried became statistically nonsignificant (in relation to heart disease) when thrown into a model with wheat.

Income is positively associated with heart disease when wheat is held constant, but it still doesn’t put a ding in wheat’s association with heart disease.

Models with more variables

So apparently comparing wheat + one other independent variable isn’t enough to explain the Wheat Effect. Not even a little bit. But maybe, just maybe, a bigger combination of variables will do the trick. Perhaps wheat-eating regions just host a collection of heart-harming factors (low folate, low vitamin D, low EFAs, and so forth) that, together, are more powerful predictors of disease than the variable wheat.

Here are the variables I’m interested in looking at. Some could be causative and some could be preventative:

- Wheat consumption

- Corn consumption

- Millet consumption

- Rice consumption

- Total blood cholesterol

- LDL cholesterol

- HDL cholesterol

- Apolipoprotein-B

- DHA levels

- Folate levels

- Latitude

- Added vegetable oil

- Blood pressure

- Weight

- BMI

- Total fat intake

- Total monounsaturated fat intake

- Total polyunsaturated fat intake

- Total saturated fat intake

- Percent of calories as fat

- Percent of calories as carbohydrates

- Total animal protein intake

- Total plant food intake (by weight)

- Total animal food intake (by weight)

- Green vegetables (daily, not yearly)

- Vitamin C intake

- Total sodium intake

- Poultry consumption

- Egg consumption

- Red meat consumption

- All meat consumption

- Fish consumption

- Dietary cholesterol intake

- Percent of the population currently smoking

- Percent of the population who have ever smoked tobacco

- Percent of the population smoking manufactured cigarettes

- Percent of the population pipe smoking

- Percent of the population smoking cigars

- Percent of the population working in industry (typically less physical activity)

- Percent of the population working in agriculture (typically more physical activity)

I won’t bore you with the results of every single combination I tried (over 100), so here’s the gist. No matter what model I use, wheat always adds unique variance. That means wheat (or an undocumented variable associated with wheat) is contributing something to heart disease that these other variables can’t account for. No combination out of the above bumped the association between wheat and heart disease out of the “statistically significant” zone.

Incidentally, one model had the best fit out of all the others for explaining heart disease:

- Wheat consumption (beta = 0.62, p<0.001)

- Apolipoprotein B (beta = 0.38, p<0.001)

- Total cholesterol (beta = -0.22, p<0.05)

Note that the number for total cholesterol is inverse, meaning higher cholesterol was associated with less heart disease—at least in this specific model. Unless you’re an Ancel Keys groupie, this may actually be quite plausible.

Anyway, here’s the important point. No matter what variables I adjust for, I can’t make the correlation between wheat flour and heart disease go away. Sorry, wheat! Neener neener.

Cardiovascular disease: The only “Western” problem without “Western” risk factors

Here’s a mystery for ya.

In the China Study data, most Western diseases (such as breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, and diabetes) are concentrated in areas that share some key characteristics: more industrial employment, less agricultural work, greater population density, and often higher levels of schooling. Folks here eat more processed starch and sugar, use more polyunsaturated vegetable oils, chug down more beer, smoke more manufactured cigarettes, and typically get less physical activity than their neighbors in pastoral communities.

In other words, the Western-disease-prone-regions are like baby Americas—slowly waddling, diapered and naive, towards the motherly lap of disease.

Most likely, these Western ailments aren’t spawned from a single food or activity, but from a tragic mix of diet choices, lifestyle habits, and environmental factors. For problems like breast cancer and colon cancer and lung cancer, it’s pretty easy to see what the matrix of risk-raisers are from looking at the data: It’s the same combination of things spurring disease in Western nations.

But oddly enough, this isn’t the case for heart conditions. The factors shared by other Western illnesses are not, in most cases, associated with heart disease in this data set. If you’ve read some of the earlier China Study posts, you might remember that I took issue with Campbell’s disease-clustering strategy because heart disease doesn’t fit cleanly with the “diseases of affluence” group, despite his insistence on sticking it there anyway. Unlike the other Western problems, heart disease isn’t associated with eating more sugar, working in industry, drinking more alcohol, using vegetable oils, having higher apo-B levels, or any of the other variables uniting the Western diseases and mirroring the traits common to industrialized countries.

What’s the only thing heart-disease-prone regions have in common with Westernized nations? That’s right: consumption of high amounts of wheat flour.

Food for thought. Kinda spooky.

Wheat eaters: fatter with fewer calories

Here’s some more weirdness. In both China Study I and II, wheat is the strongest positive predictor of body weight (r = 0.65, p<0.001) out of any diet variable. And it’s not just because wheat eaters are taller, either, because wheat consumption also strongly correlates with body mass index (r = 0.58, p<0.001):

How odd! This aligns with a post Stephan Guyenet at Whole Health Source wrote about wheat consumption and obesity in China, speculating that wheat might wreak metabolic havoc wherever it goes—a trend that becomes apparent when comparing similar populations of wheat eaters and non-wheat eaters, such as in China. But perhaps there’s some confounding going on. What about calorie intake? Are the wheat eaters just scarfing down more food in general, leading to higher weight regardless of wheat consumption? Doesn’t look like it. Running wheat and calorie intake together as predictors with BMI as the outcome, wheat takes the weight-gaining gold:

- Wheat: beta = 0.56, p<0.001

- Calorie intake: beta = 0.13, p = 0.19

Unfortunately, we have no way of accounting for energy expenditure through physical activity—but considering wheat-eating regions tend to be pastoral and dominated by agricultural work, it seems they’d be burning through a greater wallop of calories than more sedentary regions. Indeed, independent of calorie intake, there’s a clear association between agricultural work and weight (lower) versus industry work and weight (higher), suggesting these things could be approximate measures of calorie expenditure. So once again, we’ve got a paradox: The wheat eaters are consuming lower or average levels of calories, doing more physical labor, and yet… they’re fatter.

Out of curiosity, I ran a stepwise regression on a bunch of relevant variables to see what combination would best predict BMI. (In statistics, stepwise regression is a really cool, but sometimes totally misleading method for building a statistical model. It involves adding (or winnowing away) variables one by one based on how they behave together and contribute to the outcome—BMI, in this case—until you’ve got a model where each variable offers significant variation and the highest possible percent of explanation (represented as r-squared). Unfortunately, since this process is automated and computers usually don’t understand the whole “biological plausibility” thing, you can wind up with weird models that don’t make sense in the real world. Nonetheless, it can be a worthwhile method if used with caution.)

Setting BMI as the outcome, I chose the following variables as potential exposures:

- Total calories

- Total fat

- Total carbohydrates

- Total plant food

- Total animal food

- Total plant protein

- Total animal protein

- Total monunsaturated fat intake

- Total saturated fat intake

- Total polyunsaturated fat intake

- Red meat

- All meat

- Fish

- Poultry

- Eggs

- Wheat flour

- Corn

- Millet

- Legumes

- Starchy tubers

- Green vegetables (daily, not yearly)

- Agricultural employment

- Industrial employment

(I left out milk because so few counties consumed it.)

The best-fitting model for predicting BMI (at 95% confidence)? Drum roll please. Three variables made the cut.

- Eating more wheat flour (beta = 0.48, p<0.001)

- Eating more polyunsaturated fat (beta = 0.44, p<0.001), and

- Eating fewer green vegetables (beta = -0.29, p<0.01).

This model has an r-squared value of 0.53, meaning it predicts a little over half of the variation in BMI—at least in theory. That’s actually pretty high, considering we haven’t directly factored things like physical activity into the equation.

Interesting, eh? All animal foods and total dietary fat, by the way, were completely insignificant in terms of BMI.

Of course, there could be other variables involved that the China Study didn’t cover. Were the higher-BMI folks also more heavily muscled (perhaps from more physical labor), increasing their body weight but not body fat? Are the wheat eaters, some of whom are ethnic minorities in China (especially Turkic and Mongolian), genetically “bigger” than the Han Chinese? There are plenty of unknowns, and alas, no way to clarify them based on this data.

I guess we’ll leave it as a question mark for now.

Grain damage: Do other studies back it up?

But don’t those peer-reviewed, scientific studies tell us wheat is healthy? Alas, the vast majority of studies on grains—especially wheat—showcase at least one of the following problems:

- They look at the effects of whole grains versus refined grains—not whole grains versus the same diet with no grains at all.

- Study subjects increase their consumption of whole grains, and this displaces some portion of yuckfoods (processed junk, white-flour products, sugary things, and so forth). As a result, it’s hard to tell whether any health perks are due to the addition of whole grains, or from the reduction of truly-awful-for-you foods. This is particularly true in studies that scout out disease patterns in populations rather than controlled studies that measure specific changes that occur with the addition of whole grains.

- They don’t adequately account for other factors that often accompany whole-grain consumption, like a greater level of health consciousness, more exercise, other positive diet choices, and so forth.

However, a few gems are lurking in the massive slush-pile of irrelevant studies. This one’s pretty doggone interesting, and it’s from all the way back in 1959: “Comparisons of atherogenesis in rabbits fed liquid oil, hydrogenated oil, wheat germ and sucrose.” You can click on that for the full-text PDF.

As you might guess from the title, this study examines the effects of diet on the development of atherosclerosis—AKA hardening of the arteries. The researchers took cholesterol-infused rabbit food and supplemented it with liquid corn oil (yuck), hydrogenated corn oil (double yuck), wheat germ (mystery murderer?), and sucrose (sweet poison!). Sorry, I dig hyperbole. Anyway, part of the goal was to create an experiment testing the hypothesis that “the geographic differences in the incidence of coronary disease might be related to selective hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids or to degermination of cereals.”

So now, the moment of truth: Which group had the most severe atherogenesis? Perhaps the one fed the nasty hydrogenated oil, as hypothesized? Ladies and gentlemen, place your bets. From the article:

The most severe atherogenesis occurred in the animals on the wheat germ diet.

Was it a fluke? Probably not:

In an earlier study, we maintained 5 groups of 5 rabbits each for three months on 500 mg of cholesterol daily and rabbit chow supplemented with different fats or with wheat germ. Here also, the animals on the wheat germ diet showed a significantly greater degree of atheromatous lesions than the animals on rabbit chow plus 20% corn oil, cottonseed oil or hydrogenated cottonseed oil, whereas no significant difference was found between the various fats.

So what made the wheat germ contribute to atherogenesis? The researchers state that it’s “difficult to speculate” about the mechanism, which is a scientific way of saying “We dunno.” They suggest the extra dietary protein from wheat germ could be the cause, but from the literature I’ve skimmed so far, it looks like plant proteins don’t have much effect on bunnies (although animal protein does).

Of course, rabbits are truly terrible models for anything that happens in the human body. They’re hardcore herbivores. A mere billowing of the wind is practically enough to spike their cholesterol. But what explains the specific effect of wheat germ on their poor arteries? Could this have implications for humans?

My answer: It’s “difficult to speculate.”

Other studies

Prefer human studies? Me too. Here’s one that initially looks totally irrelevant but is actually pretty interesting: Flaxseed and cardiovascular risk factors: Results from a double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. (This also a stellar example of why it’s important to read full-text articles instead of just abstracts, which often don’t tell you diddly about the stuff you want to know.)

This particular study charted the effects of flaxseed on adults with high cholesterol. One group got food with ground flaxseed; the other group got food with added wheat bran. Other dietary elements were the same. (Low fat, low cholesterol. Fun times!)

The results? Ye Olde Flaxseed Group did pretty well: Compared to their baseline measurements, these folks had lower insulin, lower blood glucose, lower C-reactive protein (a marker for inflammation), and better insulin sensitivity (as calculated by HOMA-IR).

But poor Wheat Group was less fortunate. Since the study was about flaxseed, the results of wheat aren’t specifically discussed, but check out “Table 4” in the link above to see the numbers for yourself. The wheat-bran eaters had a 14.9% increase in insulin resistance (calculated by HOMA-IR) and a 9.3% increase in C-reactive protein. In other words, they lost some insulin sensitivity and gained some inflammation—two risk factors for heart disease. Hmm. Was the wheat bran to blame? Some other element of the control diet? It’s impossible to say for sure based on this study, but considering the wheat group’s adverse effects were more dramatic than the flaxseed group’s benefits, it seems a little suspect.

(A rather abrupt end of part one! The next post will have some more studies and speculations on potential mechanisms for wheat as causative of heart disease.)

Also! For anyone who wants to analyze the online data, HUGE WARNING: If you open the stuff in Excel and then try to copy and paste into another program (I’ve been using SYSTAT), be very, very careful that it transfers correctly. I kept having the bizarre problem of about 10 blank cells randomly inserting themselves into each column of data once pasted, typically after line 400 or so. I have no clue why. But it was a total headache. It causes some of the data to be misaligned, so any attempt to analyze different variables is inaccurate. Again, headache city! Avoid it if possible! Adieu.

Thank you, Denise, for this magnificent effort! This is way more informative and more fun to read than 99% of the articles I plow through in the medical journals I read.

Neisy, I have a q……with regard to correlations on disease and food consumption, where do they get all of the numbers that show direct or inverse correlations with food x or y?

Denise is feeding the data into a statistical analyser, perhaps R or some other package. This package can then carry out the kind of analysis she is talking about and it will produce the figures you are asking about.

Fascinating! Thank you for doing all that hard work. I will letting others know about this post.

There is one variable you did not mention (and may not be available): how was the wheat processed. Traditionally, in the West we ate wheat as yeast breads. (OK, so the poor also got porridge.) The Chinese like noodles — they invented them. The question that rolls around in my mind is: is wheat OK if it has been fermented?

Industrial foods don’t just strip off germ and bran, they bypass the yeast. Today we eat a lot of crackers, cookies, pasta and breakfast cereals. And even our yeast breads are shortchanged as bakeries use sugar to speed up the rising process.

I really, really, really wish the China Study had documented more specific information about processing methods. I have no idea if the wheat was soaked/sprouted/fermented/refined/etc. One woman who reads this blog actually contacted Richard Peto, one of the other China Study researchers who worked alongside Campbell, and asked for more information about how wheat was processed—but he had no idea.

For what it’s worth, wheat in Chinese noodles is typically not fermented or sprouted. Northern Chinese do eat some wheat as bread, but much that is unleavened. I’m not sure what you mean by “refined”, but the foods are made from wheat flour.

Hi Denise,

Thanks for a great read. The other thing that one should remember with these food frequency questionnaires is that they can occasionally ‘overlook’ hidden dietary intake. Obviously this is dependent on how thoroughly the questionnaire was constructed.

The reason I raise this issue is because a processed item especially used by Chinese and Japanese is soy sauce. And now, with the big sushi fad, westerners also consume this to a certain extent. To my amazement someone pointed out to me that soy sauce contains a considerable amount of wheat. I don’t know whether ‘wheat’ consumption included this hidden wheat contributor.

I tend to, just like you, try and listen to my body to see what I should eat or not eat. And wheat is one of those my body doesn’t like.

Thanks again for really informative posts.

Thanks Riaan! Fortunately, the China Study used not only food-frequency questionnaires, but also had survey crews visit each county and record food intake (by weighing, observing, measuring, etc.) which probably reduced the chance of overlooked data.

The study also recorded soy sauce as a separate variable, but there were no major correlations with heart disease — not surprising, since it’s hard to eat a condiment in the same quantities you’d eat a staple grain. (It may also be significant that the wheat in soy sauce is traditionally fermented.)

And it is possible to get soy sauce that contains no wheat, is GMO free and is gluten free. Costs more, of course.

I guess you are referring to Raw Coconut Aminos, Soy-Free Seasoning Sauce Although it is more expensive it’s possible to find 16 fl oz (473 ml) $4.10 (£2.65)

Good question. Here’s another: Is Chinese wheat a “heritage” variety, un-messed-with by hybridizers? Or is it similar to American wheat, which in the last hundred years has been changed around on the chromosomal level to be shorter, easier to harvest, higher protein, etc.?

This work should be published!

But Campbell and his devotees will complain that there’s too much cutesy grammar for it to be taken seriously. Of course even if it was as formal as Denise’s previous analysis, they’ll still find some other irrelevant thing to complain about instead of honestly discussing the statistical analysis and its conclusions.

It is published. Right here.

Re: … Excel and then try to copy and paste into another program (I’ve been using SYSTAT),

I have used Excel 2007 initially for the same data as you but gave up after loosing columns of data during save and reopen (past column 200 or so). Looks like large data sets are crashing the Mickeymouse Software. I am now using Open Office 3.2 spreadsheet, it’s slower but it works.

Regards,

Stan

Glad to know I’m not the only one who had trouble with that!

Wow. That is more than just a “wheat post”. That is really awesome.

Good stuff. Neener, neener. Although used sparingly outside of psychological research, a factor analysis might help group the variables. It would be interesting to see, for example, if a single factor loaded similar to your stepwise results. Actually, as I think about it, it would be interesting to see the entire factor structure.

Regarding your theories, and at least statistically, wheat appears to be the lone sledgehammer. Since they’re all accounting for the same variability, it might turn out to be something as simple as the displacement of the other foods. So when you eat more wheat, health deteriorates because of the wheat but also because of the removal of the other foods.

Send me an email if you want to discuss the factor analysis.

Good stuff.

Factor analysis might be interesting—I’ll see what that turns up and include it in the next wheat post. I’ll shoot you an email as well. 🙂

I think the displacement of other foods could be a factor, but I also wonder if wheat could increase the requirement for certain nutrients and independently induce deficiency. Lots of possibilities. I’ll be writing about a bunch of potential theories in the next post.

I’m sure antinutrient properties are significant, directly or indirectly reaking havoc on gut permeability, which compounds the displacement problem.

Looking forward to the email.

Wow, 134 comments! Good on you.

Hi Brian,

i would like to learn on factor analysis…I have applied the same in my analysis of 138 CHD cases and 187 controls…could you please help me out.

Re: So when you eat more wheat, health deteriorates because of the wheat but also because of the removal of the other foods.

No, because rice would have worked the same but it doesn’t!

Why?

You’d need a controlled study to determine exactly why, this is an epistemological study and therefore can only point you in the right direction for further research, it can’t by itself prove anything (this is what makes Campell’s use of the study to prove meat is bad so ridiculous).

There is a high correlation between wheat consumption and heart disease, but no high correlation between rice consumption and heart disease. From the information in the study, there is no way to tell why that is. It does, however, give a scientists a giant red flag that says “Look Here!”.

The best you can do is make a hypothesis as to why it is the way it is, based on what you know of wheat, the human body, and risk factors for heart disease. To prove anything, you’d need to run experiments designed to disprove your hypothesis. That’s why an epistemological study can’t be used to show causes, only correlations which would then be subject to further research.

Personally, the extremely strong correlation with wheat and heart disease is enough to make me stop eating wheat until someone figures out what is going on there.

It’s kinda like the fact that you don’t need to understand how gravity works to recognize that usually when someone jumps off a cliff, they die soon after. We can make that intuitive connection without needing an exhaustive understanding of why it happens.

There are issues with rice and heart disease but the relationship is not linear, it’s U-shaped. Maybe it’s protective, maybe it’s benign. In support of this, wheat and rice consumption are inversely correlated. Where low rice consumption and elevated risk are concerned (left side of the U), it might be simply that lower rice and increased wheat consumption is the problem. It could also mean that lower rice consumption absent of wheat would not be a problem. This is plausible because as rice consumption increases, wheat consumption decreases, decreasing risk for heart disease. At some point, over consumption of rice is a problem, even in the absence of wheat.

This is all very interesting. I eliminated wheat from my diet some months ago (in fact, most carbs due to impaired glucose tolerance). If wheat is really that damaging, it’s a smart move on my part! Ha Ha.

I for one, would like to see your work open sourced. I suspect there are a lot of stats wonks reading your blog (self included) and helpful in eliminating any doubt on the analysis you are reporting.

Keep up the good work.

Wow, brainwave. I’m not a stats wonk, but I’ve been following nutrition blogs the last half year or so and the bad science moniker gets thrown around a lot – and I believe deservedly so.

The challenge in my perspective has always been to conceive of a way of exchanging ideas that actually lives up to the lofty ideals of peer review scientific rigor.

In reading blog posts like this one I am pleased by all the detail, but at the same time mindful of the detail that is missing. For instance in the section of models with more variables it is mentioned briefly that more than 100 models were tried. Even if we trust that Denise would try hardest to disprove the hypothesis by focusing on the combinations most likely to do so, we would have to consider that maybe she missed one – and if someone were to ascribe less than pure motives to one such analysis not spelling out each combination that has been tried becomes attackable.

When reading that bit I thought it was a shame that there isn’t a less cumbersome (than writing out a massive text) way to convey the particulars of an analysis to an informed and critical audience. Detailed though they are we are still settling for conclusions and interpretations. This principle holds for all publications in journals that rely on statistics.

I didn’t really dwell on this missing level of communication but I guess it’s always been in the back of my mind. However, this post by PhilM following observations about the weaknesses of Excel sparked something.

I think what the scientific community (in general) really needs is a global cloud-style database where data sets from research can be published – and which can be accessed by a wide community (ideally anyone). A full palette (whatever a full palette is) of statistical tools will need to exist that can draw data from these published data sets. The configurations, analysis types, variable inclusions and whatever else is needed for statistical analysis need to be named/numbered and saved so a peer reviewer or other interested party can pick up, tweak and check an entire piece of work and as PhilM said eliminate any doubt on the analysis.

Not saying this is particularly realistic, but it’s just a bit of an epiphany to me. From not being able to conceive a mechanism that overcomes what I perceive to be a shortcoming when exchanging hypotheses and findings based on statistics through journals and in other written form I can now imagine one that would.

Instead of wondering what type of analysis Campbell used to reach his conclusions with this kind of system we could see _exactly_ what he did. It would leave scientists a lot more open to criticism, but to me that’s sort of the whole point – get rid of bad science through qualified and appropriate criticism with no smoke and mirrors being wielded. Additionally instead of saying my analysis shows x and your analysis shows y, but we can’t reconcile them because you don’t fully understand my analysis and I don’t fully understand yours… specific analytical elements could be discussed – the appropriateness of the inclusions/exclusions of specific data points or variables.

Yeah, I’m a dreamer and the point of this post is just to thank all involved with the discussion (not least Denise who keeps striving to provide a full and balanced picture) for the epiphany.

I don’t think you’re a dreamer. In fact, what you’re advocating is crucial, since the institutionalized lack of integrity in academia, where grants and tenure depend on supporting the status quo, has completely hijacked our society. Hundreds of millions have switched to unprecedented diets based on pronouncements that cannot be trusted! Seed particles, rancid (but bleached and deodorized to hide it) seed oils, and seed sugars, all produced via industrial extraction, are now the vast majority of what humans ingest — and humans don’t eat seeds!

And don’t get me started on drug research. 🙂

Until more people know how to do what Denise can do — and unmask the fraudulent omissions in pseudo-academic research — the result isn’t science, but the creation of a paid-off medieval priest/wizard class that lies to us about what the runes show.

In my view, some of the key disconnects are:

– datasets are not fully published

– papers themselves do not approach the data even-handedly, instead imposing hypotheses on the data before that’s warranted

– abstracts do not accurately describe the paper’s results! Yet only the abstract is written in a manner that can be parsed by the public and/or their jounalist proxies!

More people need to be able to read scientific papers. Michael Eades, among others, has written posts where he tries to educate laypeople on how they can be understood.

And we need more analyses by people like Denise (and Richard Kroeker’s Amazon posting) that demonstrate the gulf between the data and what the experimenters are telling the public the data “means.”

And I think publication of experimental datasets on the net ought to be an absolute requirement for funding. Cases like that of Harvard “scientist” Marc Hauser cannot be that rare — what’s rare is that the public found out. If data publication were mandatory, a lot of the scientific fraud being perpetrated would be stopped.

Campbell isn’t the only one building his career on this kind of foundation!

Don’t think Monsanto is too happy with the direction this discussion is taking….neither is Cargill. Maybe Denise can “prove” that wheat has healing qualities, then the FDA will classify it as a drug and it will be banned.

Thanks Phil!

The data I used is all available here: http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/~china/monograph/chdata.htm

I’m also going to compile all the wheat-related variables in an easier-to-use format and post that as well, so that other people can run their own analyses on it. The data on the Oxford website is pretty unwieldy.

Phil,

I’m doing an open-source attempt at reproducing Denise’s results. The report focusing on results from this page is here: https://bitbucket.org/masonicboom/chinastudy/src/master/output/wheat.md. The full project is here: https://bitbucket.org/masonicboom/chinastudy.

Join in–it’s fun. Gluten-free statisticians of the internet, unite.

Wow, this is really incredible. Great work, can’t wait for Part 2!

Thanks Denise, looking forward to part two!

Thank you, again!

Fascinating stuff, as always. It’s too bad that we as a culture are still so focused on demonizing fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and calories in general that findings about the negative health implications of grains, and especially gluten grains such as wheat, go relatively unnoticed and unstudied.

Great work as usual Denise. The wheat issue is even more relevant than debunking Campbell’s false China Study conclusions.

In addition to the factors you listed above have you looked at the anti-nutrients Phytic Acid and Lectin? Phytic Acid is a chelator of the minerals Calcium, Magnesium, and Zinc as well as the vitamin Niacin. I’m sure it’s no coincidence that Calcium and Magnesium are very important to heart health. Zinc has been shown to prevent atherosclerosis and Niacin lowers triglyceride levels.

Now take lectins. Lectins are very inflammatory and inflammation is a key factor in heart disease. It is also a key factor in metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance, belly fat, diabetes) and these are all risk factors for heart disease. Lets keep going, inflammation is a primary reason that arteries develop fissures which are then plugged with sticky cholesterol and eventually lead to clogged arteries. The vast majority of heart attacks aren’t caused by complete blockage of arteries. They are caused by blood clots getting stuck in these compromised arteries. Here is the kicker, the lectins in wheat (and soy) cause agglutination (or thicker blood and clotting). The inflammation factor cannot be overlooked.

Coupled with what you wrote above any assertion that wheat is good for you should be toast.

Hi Monte,

I believe a lot of plants have lectins, and they are all not necessarily bad for you. I think many can be destroyed with proper cooking. I believe some of the interesting things about wheat lectins are that they appear to be resistant to heat (making cooking them out more difficult), and they are insulin-mimetic (which could maybe also be involved in the increased BMI).

Thanks Monte!

Coupled with what you wrote above any assertion that wheat is good for you should be toast.

Pun intended? 😉

Pun? What pun? >:)

A lectin, basically, is a protein with a sugar molecule on one end. They cause the trouble they cause, when they cause trouble at all, because sometimes they are able to fit into receptors on cells. (Cell receptors, by the way, if I’m not mistaken, are also sugar molecules.) The trouble with wheat lectins is they are very compatible with certain cells in the lining of the GI tract. I learned about this stuff from Peter D’Adamo, the Blood Type Diet guy. I don’t know how good his science is generally but I followed up what he said about lectins and he seemed to be spot on about that. He thinks how badly a given lectin affects a person depends on their blood type since that may influence how their cell receptors are shaped.

But from what he said, wheat’s bad for pretty much everybody. Bad scene.

Awesome post.

I especially liked how you proposed a hypothesis and went about trying to disprove it – actual real science. Nutritional science has been controlled by hacks way too long who are scientists in title only.

Looking forward to part II although I have a feeling I know how the story turns out.

Thanks Denise. One wonders what the causive factors are? It is breakdown of the tight-junctions in the intestine allowing more pathogens to form biofilms inside the lining of arteries, or perhaps gluten exorphins causing signalling problems in the paracrine system?

The next post will be discussing potential causative factors. Unfortunately, there’s so little research out there looking for harmful effects of wheat or grains that it’s all theory and speculation at this point!

Once again you’ve left my wheat-free math brain happily buzzed.

Glad to buzz ya.

What a superb prelude! You have a phenomenal ability to analyze the heck out of something and then fully acknowledge that the limitations of your model, which requires a level of humility not easily found.

It’s also unambiguous evidence against the theories bound to pop up any moment now that this work was funded by the millet industry.

Thanks Chris! (I definitely read that as “mullet industry”—maybe it’s time to stop staring at the computer screen for a while…)

Either that or you need to stop watching so many 80s movies.

That’s OK. Just remind them that millet is a goitrogen if not properly fermented and de-hulled. 😀

Hey Dana,

Millet is actually goitrogenic no matter what you do to it, the goitrogens exist in both the bran and the endosperm, and traditional processing such as fermentation and cooking dramatically increase the goitrogenicity of millet, which is why the traditional cultures in the Sudan using these methods have extremely high rates of goiter, and why the Sudanese relying more on wheat and sorghum, whatever the merits of those two grains, have much better thyroid health. Millet damages thyroid tissue and inhibits basically every step of thyroid metabolism. It is a much broader-spectrum thyroid toxin than soy, cruciferous vegetables, or cyanogenic glycosides, and from among these it is the only one whose effect cannot be overcome by extra iodine.

The least goitrogenic form of millet is actually raw millet, though I’m not sure how appetizing or healthy that would be.

I have reviewed the literature on millet goitrogenicity in my Thyroid Toxins Report, a summary of which is given free on my web site:

http://www.cholesterol-and-health.com/Goitrogen-Special-Report.html

Chris

Thank you for another masterful analysis!

You are providing confirmation–from an unexpected data source–of what I have been witnessing: Wheat causes heart disease; wheat removal stops or reduces heart disease (meaning coronary atherosclerotic plaque).

I believe that the mechanisms are several, but I believe it principally involves wheat’s inordinate provocation of small, dense LDL. More than any other food, wheat provokes small LDL production, though the precise mechanism is unclear. It may also be due to wheat’s unusual capacity to provoke endogenous glycation, i.e., glucose modification of proteins. In fact, small LDL (provoked by wheat) is unusually subject to glycation (provoked by wheat). Put it all together and you have a highly atherogenic food substance.

Keep up the fabulous work!

Thanks for stopping by, Dr. Davis! Your blog is fantastic!

This is awesome. I am impressed by your work. I do have to add, “Do you ever sleep?”

Not if her boyfriend has any say in the matter. 😉

(Hey, that wasn’t any more sexist than remarks made by a major, major scientist with many publications under his belt…many of them non-fiction!)

HA! Rawr.

Incidentally, “The China Study” was published by a company that specializes in fiction and pop culture (including “Psychology of the Simpsons” and “Seven Seasons of Buffy”) –> http://www.benbellabooks.com/smartpop.php

That association doesn’t really tell us anything either. There’s far more wisdom in the screenplays for the Simpsons and Buffy The Vampire Slayer than from Campbell’s writings.

No.

wheat eaters fared WORSE than SMOKERS? and all the other factors??? and the bunnies (1959 study) worse than HYDROGENATED CORN POISON … (i mean oil…)

your further entries are anticipated with baited (nuts, a little meat, some veggies) breath–

thanks SO much Denise-

moksha

Thanks moksha!

I wonder if that was the same bunny study that was part of the “evidence” used to “prove” that cholesterol kills human beings? If so, learning about these additional food ingredients is an eye-opener. Oh let’s focus on the CHOLESTEROL already… did no one think to be alarmed about the wheat germ?

An r of .58 is not convincing. Thats an r^2 of .3364 or 33.6% chance that wheat is even associated with morbidity. I wouldn’t call a 33% chance strong. True the association between smoking and bladder or lung cancer is only 49%, but there is a lot of evidence pointing to biological plausibility and mechanisms behind smoking increasing risk for lung cancer.

No research exists on the biological mechanisms for what your hypothesizing. Yes, the epidemology showed a possible association between the two factors. Yet, we aren’t even sure if they are indeed associated, let alone if the association is even important.

The data does suggest more study of wheat consumption is needed. Although there is nothing in the data that will allow you to make any conclusions.

“The data does suggest more study of wheat consumption is needed. Although there is nothing in the data that will allow you to make any conclusions.”

yes greg – she already has said that as a clear disclaimer in the text…

(and frankly, 33% is fairly convincing data-risk for me – 2 bullets in the chamber of a “6 shooter” roulette? i’ll pass)

yes – more study is needed- but will such study ever happen? it’s akin to any other of our misguided and mistaken mass-market “lock-ins” of our modern world (querty keyboard, unquestionable worship of vaccines, microsoft windows, deification of cow’s milk) – who will dare verify this negative data on this staple of our civilization in the face of the astronomical nutritional and social changes it would entail – not to mention having to face the wrath of the mega-corporations that support all the related products?

if proven by a brilliant researcher to be true – it could likely be the last act of his/her career much less his/her life.

that said, i hope there is enough brave souls in science/nutrition to try.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture will most certainly object to any conclusions that wheat is murder. After all, they have been pushing us to eat more carbs with their food pyramid for the last 40 years, encouraging farmers to grow more wheat, corn and soy, exporting a lot of that to other countries and converting all that corn into high fructose corn syrup.

I love cow’s milk. We kill our cattle way too young now–hunter-gatherers go for the older, slower animals, who are also invariably fatter than the rest of the herd members. Young food animals = slender food animals. It’s either fatten them with grain, which is bad for us, or eat them lean, which is also bad for us, because animal protein not backed by animal fat can lead to rabbit starvation if there are also insufficient carbs in the diet. Plus, animal fat’s just plain necessary for human health.

So cow’s milk is an acceptable substitute for the fat we were supposed to be getting along with our meat. Grass-fed cow’s milk is by far the best of all cow’s milk, with a nice complement of vitamins K2, A, and E.

If you’re lactose-intolerant, butter does not contain lactose, and cheese and cream contain very little. If you’re casein-allergic, I’m sorry.

Greg,

The r and r-squared value have nothing to do with the chance or probability of an association. The r value represents the extent to which the data points fall tightly around a straight line and the r-squared value represents the proportion of the variation of one variable (heart disease mortality within a region, in this case) explained by another (mean wheat intake within a region, in this case).

This is not a probability statement or a chance of anything. The p value, which indicates statistical significance, allows a probability statement. According to the probability theory used by standard statistics, the probability statement for a p<0.05 is that if there were no relationship between the two variables, and we were to take repeated samples over and over, fewer than five percent of them would generate an association with the strength observed in this sample. Consequently, we say we are more than 95% confident that the association is true.

An r-squared of 34% by contrast means that wheat intake accounts for 34% of the variation in heart disease mortality.

And, of course, as Denise acknowledged, absolutely none of these even imply a causal relationship, regardless of whether one is plausible.

Chris

^ What he said.

I believe that you are confusing R squared with p values.

Biologically plausibile…I recommend you duck over to Dr Eades blog, or look up William Davis.

I’ve heard that logic so many times: “We don’t understand the mechanism for X, so the data is not meaningful.”

In fact, after I gave up wheat and found so many health improvements (reproducible!), a PhD biologist told me I couldn’t give it up because he didn’t understand the mechanism for what had happened to me.

That was his problem. I wasn’t going to make it mine by sacrificing my health because of his ignorance.

You see, there is a difference between understanding how the engine of a locomotive works and deciding it’s a good thing to get off the tracks when it’s coming your way.

Physicists still don’t understand the mechanism of gravity either, but that doesn’t mean that releasing a bowling ball over your head won’t cause any damage.

I think you’re confusing r-squared with the p-value: R estimates the proportion of variance predicted; p measures significance. An r-squared of 33% for a single food in relation to heart disease, especially when no other factors seem to diminish that relationship, is *extremely* high—especially given the complex etiology of heart disease.

There isn’t any research on the biological mechanisms, but that doesn’t mean that the biological mechanisms don’t exist—we just don’t have a scientific culture willing to explore this sort of thing right now, especially given how much wheat (and corn and soy) is subsidized. The economic repercussions of pinpointing a wheat-heart disease link would be devastating.

I agree there’s nothing in the data that could warrant drawing conclusions—I hope I’ve emphasized the limitations of epidemiology in a way that makes that clear! If not, I’ll say it again: “Epidemiology kinda sucks.” There ya go. 😉

Sorry to be finicky (but I forgot what R-square was until you mentioned it):

R-square measures the amount of variation within the data explained by the model.

So if you have a R-square of 0.33 says that 33% of the variation within the response variable can be explained by this model.

Or, in English, 33% of morbidity can be explained by wheat alone.

Greg said:

“No research exists on the biological mechanisms for what your hypothesizing.”

Ummm, not so sure about that Greg. I’ve been researching lectins in the context of their effects on the gastrointestinal system, specifically on villi and interferences with the immunoglobulins. I keep bumping into references to endogenous lectin pathways, the endothelium, the complement system and inflammation. I’ve disregarded them while continuing with research concerning the epithelium but there sure seems to be a lot of material out there on it. Don’t you just hate it when stuff gets in the way of your study of stuff? Given that the body has it’s own lectin systems, what would the possibility be that certain exogenous lectins may have an effect on them? Mmmm, the possibilities are so tantalizing they’re almost tactile. Not to mention that the body possesses a number of glycoproteins that are involved in cell signaling. Now the possibilities are beginning to seem endless.

Denise has mentioned a correlation with wheat and insulin sensitivity. Some lectins appear to have the ability to affect the insulin system. I suspect that Denise isn’t blindly teasing out correlations in this area so you might give her a little space on this one. One of the effects of hyperinsulemia/hypoglycemia ( I forget which at this point) is mineral dumping. Specifically magnesium, of which one of it’s more common molecules found in the body is an extremely potent anti-inflammatory, on par with if not exceeding glutathione because it’s not made in the quantities that glutathione is. And isn’t CHD an inflammatory disease, specifically of the intima? Hasn’t magnesium been implicated as a player in CHD along with B6? The pathways are there for that possibility to express itself.

Frankly, since degenerative diseases (diseases of affluence) are progressive, it would be interesting to see some regression analysis on age, but then we already know that they present after middle age generally.

If you’d like to sink your teeth into a little more of the meat of this subject see http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6823/5/10.

Kyle

ohhhh – just had one more mischievous thought – you must be amused, at least a little, niesy – that dear ol’ doc campbell is [undoubtedly] as attentive to your new posts as the rest of us “fans”…. 🙂

keep stirrin the pot– (yes – that’s blatant cheer-leading for all you detractors…)

Well hopefully Campbell will get some lessons in how to run proper statistical analyses.

Sorry, I am not a scientist so I did have to gloss over your blog. Forgive me if you covered some of these questions…

Hasn’t wheat been genetically modified over the years? Could that be a factor in this problem? Also, wheat is in everything at the grocery store from pasta sauce to frozen fries. Could it just be the massive quantities of wheat in everything rather than just ‘everything in moderation.’ Surely someone who ate just a sandwhich at lunch and a small bowl of bran flakes in the morning couldn’t expect wheat to cause their heart any trouble.

I have heard also in terms of the gut rather than the heart, that yeast is no longer used in breads. To quickly mass produce bread, they have used some other raising agent that has lead to gut problems.

Dr. William Davis has written about how modern wheat differs from ancient strains both genetically and in its effects on our physiology. All n=1 experiments, of course. But in short, while the primordial strains aren’t exactly health food, modern “whole grain” wheat is a complete horror show:

Emmer test:

http://heartscanblog.blogspot.com/2010/06/in-search-of-wheat-emmer.html

Einkorn test 2:

http://heartscanblog.blogspot.com/2010/06/in-search-of-wheat-another-einkorn.html

Einkorn test 1:

http://heartscanblog.blogspot.com/2010/06/in-search-of-wheat-einkorn-and-blood.html

Wheat has definitely been modified (again and again and again), which does beg the question—has the quest for high-yielding grains caused unanticipated repercussions for health? I’ll be writing more about this in the next post. Ancient forms of wheat do seem to be far less harmful than modern varieties.

Quantity could certainly play a role as well, especially when most people are eating wheat that hasn’t been prepared to minimize phytate and lectin content.

… and after being discouraged from doing it yet again in the US – monsanto is apparently working with australian farmers to get their nasty little gm mods into the already nasty modern wheat for an even nastier big mac bun…

http://monsanto.mediaroom.com/intergrain-monsanto-new-wheat-breeding-collaboration

eeeeek!

I don’t think wheat was ever good for anyone. It’s in the fossil record:

Click to access mistake_jared_diamond.pdf

My opinion is that the history of agriculture is humanity trying to develop a healthy diet that is primarily supported by grains. Grains were processed to reduce the toxins and this was supplemented by gardening and animal husbandry. Maybe the French developed this system to it’s highest form.

Unfortunately, we have started on a whole new frontier of industrial food. It’s assembled from it’s components. I think the big finding is that we really don’t know what we are doing. Just looking at carbs, protein, fat, and some vitamins is a gross oversimplification. You get something less than the sum of it’s parts. Maybe this will be figured out someday, but in the meantime it’s back to basics for me.

Look into the field of paleopathology sometime. Paleopathologists can tell, just by looking at skeletal structure, whether the ancient remains they are studying come from a farming or a foraging (hunter-gatherer) people. Farmers are almost universally shorter, more incompletely developed skeletally, and show more bone lesions, meaning more disease during life.

And that’s with ancient grains, not modern hybrids.

Crowding is a possible explanation for the disease, but Weston Price noted that populations exposed to tuberculosis but who ate traditional diets rather than industrial had a greater resistance to TB.

I just want to thank you, Denise, for all of your great work!

The wheat of today is so much different that what was grown even 20-30 years ago, now with even higher gluten content. A person should be terrified to step into a bakery in today’s world! Read the label on most commercial bread, and you will find that manufacturers even add extra gluten flour to the mix.

Also, genetically engineered wheat is definately in the future, as Monsanto is now working with Australian wheat breeders to further warp the plant. “The North American wheat industry has argued that it needs GM wheat in order for the crop to remain a profitable alternative to other cereals”.

http://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Financial-Industry/Monsanto-invests-in-collaboration-with-Australian-wheat-breeders

I stopped eating all grains 18 months ago, have lost 30 pounds thus far (only 10 more to go) and will never go back. I feel better at 50 than I did when I was 40!

Jenny, that’s fantastic! Congrats on the weight loss! At this rate, I bet when you’re 60 you’ll feel better than when you were 30. 🙂

That Wheat Is Murder image has me in stitches. It’s the best, most clever, co-optation I’ve seen in ages. Sure to get under the skin of blowhard holier-than-thou activists everywhere! I would totally rock a t-shirt like that. 🙂

Borrowing from an ol’ Propaghandi song, maybe it could say ‘wheat is still murder and berry is still rape.’ (or grape?)

Chris

Yes, like the rest of Denise’s output, it’s absolute genius (if a bit cutesy and girlish.)

Sorry, couldn’t help myself. 🙂

http://shop.cafepress.com/wheat-is-murder

hey – lighten up on the “cutesy and girlish” thing – why must we be bored to tears by deadpan, dry and chalky old “scientific” bla bla just ’cause this is a somewhat obscure/intellectual discussion?

it does not diminish the message one iota – and keeps (i am sure) more than just me coming back since i, for one, can readily admit that i don’t understand (in detail) a good bit of the statistical jargon!

niesy, cutesy on– 😉

(PS to niesy- a little teeny primer tacked on to the analysis on the range/value/significance of the numbers you are tossing about would, in fact, assist statistics neophytes like myself to glean just a bit more than the basic message. now, i’m not sayin’ that “WHEAT IS MURDER” is not pretty percipient – but maybe some simple guide to what constitutes a “statistically significant” number value, etc etc – thanks)

Denise,

Have you seen Brad Marshall’s review of the data on how saturated fat is associated with less CAD (heart disease) in the Tuoli province?

I am looking eagerly to your thoughts… Strong work on your presentation!! Keep up the edification and education for all. Thank you for all your SLAYING… 🙂 You rock, grrrrl!!

http://drbganimalpharm.blogspot.com/2010/07/great-tragedy-of-science-slaying-of.html

-g

why must we be bored to tears by deadpan, dry and chalky old “scientific” bla bla?

Because it’s the figleaf we’re holding over our tiny, withered scientific integrity?

Holy cow! You obviously put a lot of work into this. I just want to say, thank you for doing this… it is fantastic work on a very important topic. I support this 100%.

That was amazing.

Now to stop eating the damn thing.

Unfortunately, its too difficult to avoid :-(.

No its not. It just takes discipline.

But to start, ditch pasta and bread and cook most of your meals at home. When you eat out, get sandwiches without bread if you have to buy lunch, or buy a meal with a side salad or vegetables (i.e steak or fish).

Removing wheat has improved my health considerably.

I didn’t find it difficult, either. You just have to let go of the things you can’t eat anymore and embrace all the wonderful things you still can – including a lot you may never have tried before.

No I don’t eat those things.

I am an Indian, we have very different things that we eat.

When I do go to friends or relatives, it gets difficult.

Sometimes, there are some sweets with tiny bits of it. And I do have a sweet tooth, however well controlled.

People here have the same problem: wheat can be found in almost anything, and often people who offer you meals make no effort to accommodate you.

But the fact is that your feelings toward this issue play a big role in whether you find giving up wheat to be easy and straightforward, hard and limiting or absolutely impossible.

I prepare almost all my food at home from basic ingredients. When I visit people, I often eat before the meal or bring food for myself, explaining that I don’t want to inconvenience them with my dietary restrictions.

I never go anywhere expecting to be able to buy food. I always bring it. There is no gluten in my house.

You have to find what will work for you. It’s a matter of your health.

Re Monte Diaz’s comment

Evidence of decreasing mineral density in wheat grain over the last 160 years.

The concentrations of zinc, iron, copper and magnesium remained stable between 1845 and the mid 1960s, but since then have decreased significantly, which coincided with the introduction of semi-dwarf, high-yielding cultivars. In comparison, the concentrations in soil have either increased or remained stable.

Thank you for bringing up an important point Mr. Hutchinson. I would add that the phytic acid wheat ironically binds and makes unavailable the very minerals it is supposed to give us.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8829129?dopt=Abstract

But not only has the mineral makeup of wheat been depleted but the mineral content across the board from all intensively farmed crops has been depleted.

Click to access Yields2Pager.pdf

If you take a look at the USDA’s own data you’ll see that we have to eat 10 to 15 cups of leafy vegetables to get our daily allowances of the tested minerals not to mention the trace minerals. If you notice the daily recommendations have been going up and up for servings of vegetables with advocates now reaching for 10 to 20 servings. In an evolutionary sense this cannot be normal. We don’t have the teeth nor the stomachs to eat this way. Its more likely that the two to three servings that we do eat per day at one point in time (wild fruits and vegetables) did provide us with enough antioxidants, minerals, and vitamins to be healthy.

A couple of things we can do….

1. Support the remineralize movement. http://www.remineralize.org/

2. Buy organic non-intensivly grown produce from local farmers markets.

3. Grow your own heirlooms and supplement your soil with products like “ocean grown”.

Brilliant work. Don’t change your writing style. It will be read by more people than the dry and dusty works. And you link to the dry and dusty stuff if people want to read it! LOL.

I gave up wheat a few months ago. I’m hoping my flaxseed muffins are still safe.

Fine analysis, but anything less was not expected, seeing how good you’re previous work was. As for the danger of wheat germ, you can read on Petro Dobromylskyj hyperlipid blog (http://high-fat-nutrition.blogspot.com/) a lot about the possible mechanism of its dirty deed.

http://high-fat-nutrition.blogspot.com/search/label/Wheat%20Germ%20Agglutinin%3B%20how%20little%20is%20enough%3F

and especially

http://high-fat-nutrition.blogspot.com/search/label/Wheat%20and%20lactose%20%281%29

Bravo!

(And bravo! as well for delivering all this fascinating math-y info in a sweet and fun-to-read way.)

CHINA STUDY: Which diet components are associated with more and less vascular disease mortality? – http://www.canibaisereis.com/2010/08/07/china-study-diets-associated-with-vascular-mortality/

Interesting analysis. An interesting fact though is that in India, at least in the 1960’s and 70’s, the overall pattern was reversed so that the wheat eating Northern regions had 1/7th the coronary heart disease rates of the rice-eating Southern regions.

The north and south also differed in that the northerners ate more sugar and much more fat (about 22% of calories, mostly dairy and ghee; the southerners ate only 3% of calories from fat). The Northern diet was also more course and fibrous than the Southern diet. These facts are all from articles by Malhotra from 1967 through 1973.

I suspect that has more to do with the fact that the amount of wheat consumption in the north was still relatively low compared to western countries, and, most importantly, the absolutely huge amount of PUFA consumed in the south as compared to the north. Gigantic PUFA load will pummel tiny wheat load any day of the week.

There is the slightly more blatant paradox that one of the least unhealthy western nations (France) is also among the top consumers of wheat in the world, their consumption being significantly greater than the far more unhealthy UK and US.

Obviously there is more to the picture than wheat. They do have a diet very low in PUFAs.

There is clearly more to the picture than wheat.

One must keep in mind that while the wheat eating areas of China get more coronary heart disease than the rice eating areas, the rates are still far below those of the U.S.

It seems quite likely to me that overweight and obesity, or possibly caloric surplus or affluence, is an independent risk factor that is needed for the levels of coronary heart disease found in the U.S. The French are less fat, and so might get less heart disease even with more wheat.

It would be interesting to compare the French rates of CHD with those of the Chinese wheat and rice eating areas.

The Indian Chapati eaten in the north is made from a low gluten wheat variety. Monsanto was trying to steal a patent on it. google chapati gluten monsanto.

Regarding the French note that they leave the baguette to ferment for 11 hours prior to baking. in other western countries it is max one hour.

David, I am currently working in India. India has the largest vegetarian population in the world. It is also, according to the WHO, #1 in Diabetes, #1 in Cancers and Heart Disease. 60% of all heart disease patients live in India. They are following America off a cliff attached to a rocket. They have replaced their coconut oils and ghee with more carbs. They revere their doctors who are educated in the US and UK. Of course, they are all wrong. Thank you Denise! Your light is bright and I won’t screw up on my web/blog lest you burn me to ashes with your gaze.

They’re going to find that saturated fat is *heart-protective.* You just watch. Of course it’ll be another hundred years before the government and the experts admit it.

No wonder Loren Corain wrote the article called “The Whole Wheat Heart Attack”.